Well, I guess that I squeaked loudly enough to receive a substantive explanation on Thursday from PRD Editor Erick Weinberg of the paper rejection. What he said is the following:

PRD explanation wrote:Your paper was rejected because it is wrong. In order to avoid any confusions arising from the properties of spinors, I cited the example of a spinless charged particle. In response, you present a claim that such a particle would not detect a half-integer monopole. This is certainly implausible: A magnetic monopole, by definition, creates a Coulomb magnetic field. Any charged particle will certainly be affected by this magnetic field (e.g., by a Lorentz force if the particle is moving), regardless of the source of that field. The standard Dirac arguments then lead to the conclusion that such a particle will detect a singularity unless the charge of the monopole satisfies the Dirac quantization condition.

In reply I wrote back:

Yablon reply to PRD wrote:Thank you for your email of 12:38 PM today. All I really wanted was an explanation of why you had concluded that my reply was unpersuasive, and not simply a statement that it was. You provided that today, and I will now take that under advisement in a positive way. Because you have now explained why you reached your conclusion, I see no need to pursue an appeal, and so you may keep this paper inactive.

Now let's talk about the physics of all of this. I will refer to the latest draft of my paper posted at

http://vixra.org/pdf/1511.0151v2.pdf. I also want to thank guest1202 for another insightful recent post, I will get to that separately when I have a chance.

First, with this rejection, I understand the longer-term method to Weinberg's madness. He is the one who when rejecting a draft early in 2015 suggested that I explicitly derive the potentials for the Dirac magnetic monopoles as well as whatever fractional monopoles I was pursuing. I did so for the usual Dirac monopoles at (4.12), namely:

d\phi)

. (4.12)

This potential is well known, see for example, the final set-off equation at

https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/inde ... c_monopole, which is a very good reference that I urge you to read if you are trying to follow this thread. Note that I use a reversed sign convention from this reference. No tidal lock in (4.12).

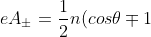

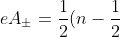

Following suit, at (5.16) I set out the monopole potential for a wavefunction which

is in a tidal lock, namely:

(cos\theta\mp 1)d\phi)

(5.16)

This is associated with my claimed half-integer Dirac monopole charges. It is easily seen that the

potential (5.16) is half a strong as the

potential (4.12).

So here is what Weinberg is really saying, and in classical physics it is a perfectly correct argument: Equations (4.12) and (5.16) are both the equations for the electromagnetic vector potential one-form of a magnetic monopole. What you, Yablon, are telling me, is that if you detect the monopole with an electron that is not tidally locked, you get the potential (4.12). But then, if you detect the same monopole with an electron that

is tidally locked, you get the different potential (5.16). But these potentials

belong to the monopole itself. They should not depend on what you put into the potential to detect things. Further, the potential will of course determine the motions of electrons and other charged particles placed in that potential, because at the end of the day the magnetic monopole -- as unusual an object as it might be were it to exist -- is still creating a magnetic field indistinguishable from any ordinary magnetic field other than the fact that it has a monopolar field

configuration, and we know from Maxwell and Lorentz how a charged particle will behave in a magnetic field. E&M 101. So how can you tell me that I can take an electron wavefunction, and have it respond as if the

magnetic monopole potential is full strength when there is no tidal lock, but is half strength when there is a tidal lock? In order for that to happen, the potential of the monopole would have to be dependent on the wavefunction itself, rather than independent of the detecting wavefunction. And we know very well -- at least in classical electrodynamics -- that subject of course to choosing a "ground" which we handle formally through gauge symmetry, the potential is the potential, and whatever particles you run through that potential do not charge the potential, except insofar as those objects generate their own potentials. Further, nobody would ever contend that if we take an electron and positron, and have them orbit each other in a "binary" system, the positron would cause the electron potential to change based on whether the electron rotated or not while these particles orbited one another. And, Weinberg is saying, the reason I had you, Yablon, lay out these potentials, is because I knew that sooner or later you would get to the point with your fractional charges that I could shoot down this whole crazy idea by pointing out that for these fractional charges to exist as you claim they do, your monopole potential could not be independent of what you are putting into the potential, and nobody ever deals that way with a Coulomb potential, electric or magnetic. End of story.

This is actually a very good argument, showing that Weinberg was looking at the chessboard several moves ahead, and in classical electrodynamics, it cannot be refuted. But now let's talk about

quantum electrodynamics. For my fractional charges to remain viable in light of the above, it would be necessary for the monopole potentials to in fact change based on how one detects them. These monopoles would have to be objects having the quantum behavior whereby

the very act of observing changes what is observed. So the very act of detecting the monopole with a tidally-locked wavefunction rather than one which is not tidally locked has the wavefunction

interacting with the monopole so as to change the quantum state of the monopole from one with a full-strength to one with a half-strength

potential. That is, the tidally-locked wavefunction has to interact with the magnetic monopole with sufficient strength over a wavefunction not in a tidal lock,

so as to literally kick the monopole into a different quantum state with a half-strength potential. This, I believe, is exactly what is happening, in physical reality. And in fact, the way in which Weinberg has rather cleverly forced me to look at this starting with explicitly laying out the the monopole potentials actually strengthens my view and the support I can bring to my view that these half integer monopole charges (and the odd-integer fractional monopole charges to which these are a waystation) are in fact what is being observed in the Fractional Quantum Hall Effect (FQHE) near absolute zero. Below, I will briefly explain how all of these puzzle pieces fit together. I am as it happens already writing all of this up; so this fits very well with what I am already doing and seeing. For now, I will simply state the theory in broadest terms. I will share this with greater supporting detail in the coming days and weeks.

As I have been maintaining and developing for what is now just over a year, at ultra low-temperatures near 0K, Dirac monopoles come into existence, and there is a formal

duality symmetry under the interchange of the electric and magnetic charge strengths coming very clearly out of the standard Dirac condition known since 1931, derived at (4.7) of my paper:

(4.7)

This is the single most important symmetry to be found at low temperatures, and although this is not yet understood or accepted by the wider physics community, it is at the heart of all of the very unusual electromagnetic phenomena which are observed in condensed matter physics when one freezes a conductive "host material" down to near 0K and then starts generating currents (superconductivity) or applying very strong magnetic fields (FQHE) while measuring what is going on. It is also helpful to think about this the other way: near 0K magnetic monopoles really do exist and lie at the root of all the unusual electrodynamics and particularly magnetic behaviors seen at those temperatures in condensed matter physics. Then, when we start to add some heat to bring the temperatures up to a few degrees Kelvin (exact temperatures being dependent on the particular host material), the monopoles melt (and in fact melt into a "thermal residue charge" which is at the heart of the partition functions used in thermodynamics leading to a direct unification between electrodynamics and thermodynamics which writing up will be my major winter project this year), and the

duality symmetry disappears / becomes hidden, not to be seen again until one gets up to the ultra-high GUT energies of the early universe where 't Hooft and Polyakov and most everybody else have been looking for magnetic monopoles. Indeed, those who have studied my posts here know that I have said for several years that the road to the unification of all of physics is paved with magnetic monopoles. Up until a year ago I spent several years showing how baryons are themselves the topologically-stable magnetic monopoles of Yang-Mills theory following spontaneous symmetry breaking, and used this to explain the binding energies of fifteen (15) light nuclides from isotopes of hydrogen through nitrogen to parts per million relative to observational data, and to explain the proton and neutron masses in relation to very precisely-specified quark masses within all known experimental errors.

But let's get back to

_{em})

monopoles and the tidal lock business. Dirac was also the first to point out that although his monopoles possessed a

duality symmetry, this was not a complete symmetry owing to the relatively weak strength of the electric charge

. Indeed, using the fine structure constant

, Dirac pointed out that the magnetic force between poles would be larger than the electric force by a factor of "

^2=4692)

." So, near 0K where these monopole do exist, there will be extremely strong forces at work that evaporate just a few degrees above 0K, the precise temperature being material dependent. And what does this have to do with tidal locks? In classical physics -- think gravitation and the Riemann curvature tensor -- a tidal lock occurs when two bodies are "attracting" one another (really, the geometry is curved) so strongly as to break any perfect sphere one may mentally attribute to those bodies, and instead produce a mild or even severe bulge in one or both of the bodies along their axis of separation. The bulge, in turn, combines with the attractive "force" (really, pursuit of a geodesic path through the geometry by each infinitesimal piece of the bodies) to constrain any independent rotation of one or both bodies, and force them into a tidal lock, such as what happens to the moon in its earth orbit, aside from the libration owing to this orbit being mildly eccentric and not perfectly circular. But it is a

strong "attractive" "force" which is responsible for the bulge which in turn locks in the synchronous rotation. So, back to Dirac monopoles: When the temperature approaches 0K, what at higher temperatures were simple electrons now "condense" into magnetic monopoles containing a magnetic charge that will interact with another magnetic charges 4692.25 times as strongly as the electric charges interact among themselves. So while electric charges alone could get an electron and a positron to interact,

they are not yet strong enough to put them into a tidal lock. But when the temperature is cooled to near 0K and some of the electrons start to "go magnetic," the forces between opposite magnetic charges become sufficiently large to in fact produce a tidal lock. And the tidal lock produces half-integer charges as in (5.16) above. Then, when the temperature is raised and the magnetic charges melt into thermal charges that drive the partition functions of thermodynamics leading to thermodynamics as we know and observe it, all that is left are electrons without their stronger-by-4692.25 magnetic charges, there are no longer any tidal locks, and so the only thing we now observe are whole-integer charges of Thompson and Millikan with the whole-integer condition (4.12) which is responsible for the observed quantization of electric charge via the thermal residue from the magnetic charge which unifies electrodynamics and thermodynamics.

So now, how do I reply to Weinberg's perfectly correct classical position? We must focus on the fermion wavefunction itself which is doing the detection of the magnetic monopole. If the wavefunction is truly physically tidally locked to a magnetic monopole, then the wavefunction must itself be the wavefunction for an electron that has "gone magnetic," and so possesses the magnetic charge that will enable it to get into a tidal lock with the monopole. That is, the only wavefunction which will tidally lock to a magnetic monopole, is a wavefunction for another magnetic monopole. If the wavefunction is not tidally locked to the monopole, then the wavefunction is necessarily that of an ordinary electron which has not "gone magnetic." And as a consequence, all that will be detected is the integer charge condition. So, going back to the quantum maxim that the act of observing changes that which is being observed, the reason what a wavefunction in a tidal lock with a magnetic monopole

can and does kick the potential for the magnetic monopole into a different quantized state, is because that wavefunction itself must be for an electron which has itself condensed into a second magnetic monopole (of opposite charge), and

so is the wavefunction for a different particle than that of an ordinary electron. So, in answer to Weinberg, yes, a tidally-locked electron wavefunction

will kick the magnetic monopole potential into a different, half-integer quantum state, because by being in a tidal lock, that electron is no longer an ordinary electron, but is itself a second magnetic monopole with a charge that interacts 137/2 times as strongly as the electric charge, that then in turn does indeed cause the potential of the first monopole to move into a different quantum state. When you have a magnetic monopole interacting with an ordinary electron, the forces between them are not strong enough to create a tidal lock, so the monopole has the potential (4.12). When that same monopole interacts with an electron that has condensed into another magnetic monopole due to sufficient cooling, then that second monopole kicks the first monopole potential into (5.16), and more precisely, both monopoles go into a tidal lock and cause one another to assume the potentials (5.16). And that is where the quantum theory overcomes the classical theory when it comes to magnetic monopoles. At the same time, this leads to some very strong pair production, and this is witnessed through so-called Cooper pairing of condensed matter physics. Further, because any pair of fermions locking together will exhibit the spin characteristics of a boson, all of this gets us in the downstream development to be able to correlate spins and atomic orbital shells (characterized by total angular momentum) with fractional charge states, which will be a primary vehicle I will use to propose "spin-charge correlation" experiments that will confirm all of this.

I am looking for a good name for these electrons that have "gone magnetic." For the moment, I am calling them "magneto-electrons." So in these terms, only magneto-electrons can tidally lock together, and when they do, the strong forces between them kick them into having the half-integer quantized potentials (5.16). But when an ordinary electron interacts with a magneto-electron, the forces are not strong enough for a tidal lock, and consequently, nor are they strong enough to kick the monopole potential from (4.12) into (5.16). And that is how I answer Weinberg's perfectly-correct classical critique, which no longer holds up in the quantum world of electrons that condense at low temperatures into magnetic monopoles which are responsible for all of the unusual E&M behaviors seen in condensed matter physics. And if low temperatures cause electromagnetic charges and potentials to quantize differently, then there is also a fundamental unification of electrodynamics and thermodynamics sitting right in the middle of all this. Again, writing this up will be my major winter project this year. Not end of story!

Jay